The end of the year is coming (I started writing this at the end of 2024). Gothic winter is coming, in one of the most astounding (to me) double remakes in film history, Nosferatu (2024, Dir. Robert Eggers), a remake of the cinema classic Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (1922, F. W. Murnau), an unofficial adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, written in 1897.

Only one other director attempted a remake in that 102 year space, Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979, Dir. Werner Herzog, although important to note is the visual ‘remix’ culture surrounding it, most importantly highlighted by the other remake released in the year previous, Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (2023, Dir. David lee Fisher). Especially since the film passed into the public domain, it has been a fountain of inspiration for those who source and love film culture.

Nosferatu has had a magnetic pull on culture since the birth of it’s source material, Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula. The source novel was not in the public domain at the time, and the production studio which emerged out of the haze of post-WWI German Expression and occult mysticism, created it’s only film with the 1922 original. Although they planned to create more films at Pranafilm, it appears that the foundations of Nosferatu were the architectural ruins through which a cultural shadow was constructed, viewed through; reflected back at us. Perhaps there is something interesting, by aligning them up, and seeing what they say when ciphered through myself.

Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (1922, Dir. F. W. Murnau)

My first experience of ever seeing Nosferatu, was at a screening with my fellow contributor on the site, Ed, a dear friend. At Riverside Studios, Hammersmith, we saw someone do a one-man original score to the film and Das Cabinett des Dr. Caligari (1920, Dir. Robert Wiene). He played six/seven instruments at once, planted in the lower right corner of the auditorium. A keyboard, chimes, a flute, a drum, and more (difficult to identify in the dark). It was really unique , I had never seen film that live before, with an element of unrecorded (albeit rehearsed) improvisation. Although silent cinemas contained orchestra pits, the idea of live music accompanying films hadn’t ever connected properly in my brain before that time.

It was important to learn that the original score to the film no longer exists, what remains of Hans Erdmann’s original score is only a partially adapted suite worked on by other composers. Original scores abound throughout the decades, partially for artistic reasons and (most likely) for copyright-related matters so they could release the film for profit. A sound version, Die zwölfte Stunde – Eine Nacht des Grauens (The Twelfth Hour: A Night of Horror), was assembled without Murnau’s consent nine years later in 1930, using material he shot but never edited as well as other material shot by a different director.

It would be easy to cry foul here, but Murnau’s work was so inciendiary in it’s existence, that Stoker’s widow Florence Balcombe ordered every print of the unofficial (and therefore illegal) adaptation to be burned. Only through some prints surviving in the ether are we able to see it at all. Even throughout production of the original film, creative changes abounded. Murnau reworked part of the original script written by Henrik Galeen, coming up with the concept of theNosferatu being killed by exposure to sunlight.

Human craftwork is a constant shaped and re-shaped vortex. Artists transform the raw materials of stories, worlds, dreams, and transmute them as to their whims, their desires, their limitations. This has some unintended consequences, especially the tragedies when those artists don’t get fair payment or credit. Florence Balcombe would never live to see the film, and never recieve fair payment for the most successful adaptation’s of her husband’s work.

Some of Nosferatu’s ideas are further opaque, culturally as well as psychologically, and there has been nearly a century of volatile discussion about what the film’s psyche represents. Possible Anti-Semitic interpretations have clashed with the knowledge of Murnau’s homosexuality, of his attested to understanding of minority communities and friendship with Jewish actor Alexander Granach (who plays Knock, the real estate agent and Orlok’s aid in the film). Did Orlok represent a disfigured spectre, the image of disdain for the ‘Other’? Which ‘Other’? It seems whichever the audience wanted to project onto it, whether it was Nazi hatred for the Jewish race or for other, more diffuse ends.

Watching it again, I was struck by how much the document appears to be cinema’s open door. It contains such a rich expression of visual language in comparison to many films of this day, to many of its’ contemporaries then and now. There’s a few frames in it which are just phenomenal; the streets of the town, empty with dread, the shots of Orlok haunting the boat in his terrifying mist, and the sea itself. Murnau apparently used a metronome when filming to help control the rhythm of actor’s performance, their flow of movement and expression. To know the mechanics behind its’ construction help explore its’ depth, but it also helps crystallise or give form to explaining some of its’ eerie afterglow, it’s uncanny trance-like hold on your senses. Even though you know it not to be true, it ticks away in your skull until suddenly it is there, present. It’s roots lay in the vampiric, misty shades of occultism and the dread of a Gothic past, so it is no surprise that it continues to drain our blood.

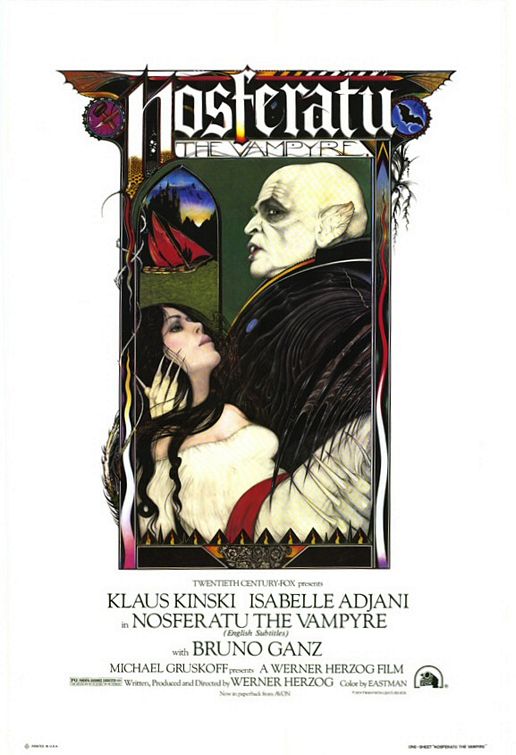

Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979, Dir. Werner Herzog)

It’s an incredible work, Herzog’s film. At times, a frame by frame remake, reconstruction, of the original. To undertake such an intense work is suitable for a man of such intense atmosphere. It purposely conjures an evocation of the original, Herzog called it the best film to come out of Germany. Now, in an age of 4K remasters, the idea of someone remaking a film so fastidiously might seem counterintuitive. The story of this cryptic vampire expands outwards with recorded sound, recorded dialogue, colour beyond tinting the actual frame with a singular hue. What might Murnau have accomplished with those tools at his disposal?

The landscape, filmed in the Netherlands instead of Wismar (the original filming location), seems vaster, the mountain passes swallowing the frame and the characters whole. Kinski’s portrayal is obsessively dark, curled and gnarled and bent by a fate of unending death. Isabelle Adjani’s ghostly, pensive stares cut through a mediatitive stillness, a disquiet of death. There is something more cutting about her presence in this, she talked about the expressions of sexuality she found evident when she holds the Nosferatu close, and her eyes portray such a fierce intensity unlike her counterpart 57 years before. Bruno Ganz’s morgue-like transformation is an expanded nightmare new to this version. He becomes a ghoul, a cruel and ironic twist of fate that Herzog felt necessary to embellish, to boil to the surface in a terrible vision.

It was sad to hear that the treatment of animals was so poor during the filming, considering their presence in the film amplifies the terror of the plague so strongly. Herzog’s commitment to cinema has been austere to say the least, but it is interesting to see what it is leftover from a time period where filmmaking was still more extensively experimental. Herzog shot with a minimal crew, only sixteen people. A small production, filmed for both English and German audiences, Rogert Ebert said about the film “Here is a film that does honour the seriousness of vampires. No, I don’t believe in them. But if they were real, here is how they must look.” Kinski endured hours of makeup application every day to replicate this doom, shadows just destroying any other sense of reality. He had to be seen, and the whole film drips and runs off him like a cloak.

The meditative patience of a film like this is only amplified by its space in cinema history, it feels like revisiting ruins centuries later, meditating in their dust.

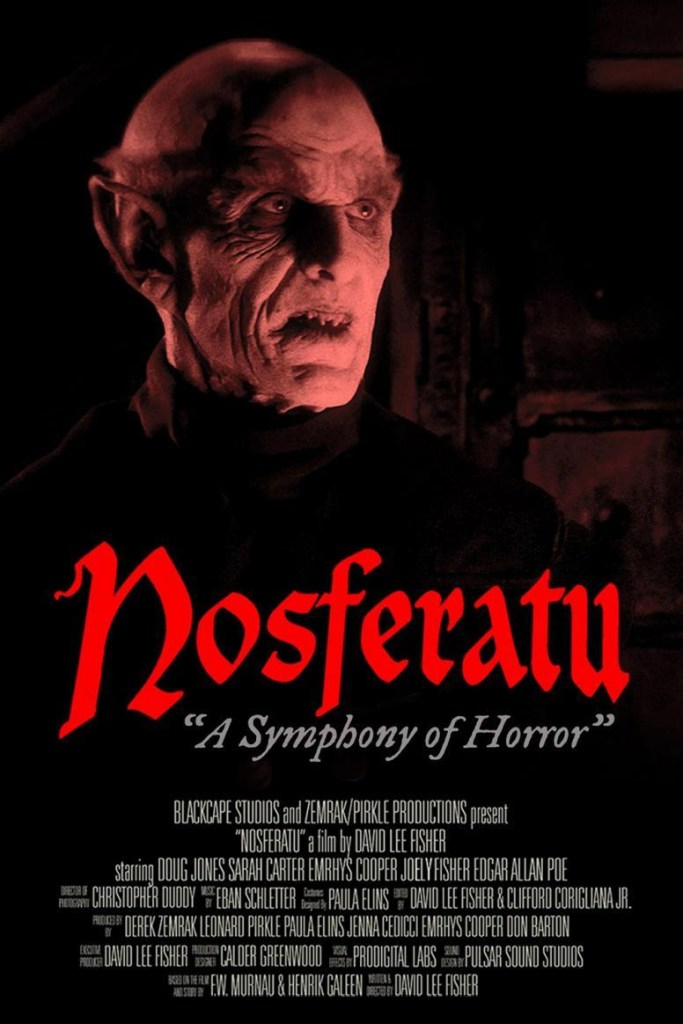

Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (2023, Dir. David Lee Fisher)

What does a work look like when it is devoid of it’s own context? The days have passed like silvery ghosts since I last wrote about this topic, this story, this nightmare. The haze of watching this work seems as foggy and surreal as the misty dawn of the Count’s ship coming in, eerie and empty.

I spoke earlier of the ‘visual remix’ culture surrounding the original 1922 film. Director David Lee Fisher spent 10 years working on this, from Kickstarter inception to surprise release in 2023. A self-dubbed “visual remix” of the original, this film used the ancient silent imagery and backgrounds of old film footage and grafted onto it modern performances captured in a green screen studio. F.W Murnau would probably laugh at the irony regarding the resurrection of his monster.

There is a different kind of reverence here for the original, expressed in Herzog’s adaptation. It is not so much about the austere spirit of the original, a kind of German confrontation of the soul through imagery. Here frames are not replicated in reality, re-staged and made to appear the same.Instead the images are fused into a collage of the old and new, and an obsession with the literal look and feel of Gothic films is cut and pasted at will with this peculiar experimental technique, some 90-100 years after the original was produced.

Murnau did not live to see the dilution of Dracula’s mythos across media, his endless replication in film & TV, all of varying quality. Everything from Hammer Horror to The Muppets. The furious case of copyright brandished by Bram Stoker’s widow against the original Nosferatu was just a minor precursor to the overwhelming stretching of the vampiric imagery across fiction and stories in general. In my lifetime, I have been submerged in vampires for so long, it hardly felt necessary to ever explore their origins. To explore Dracula felt self-evident, the image of a Count with fangs who exuded some ominous sexual presence (this element only came later as I got older). Narrative shorthand had robbed me of the desire to ever pay attention to its’ blood, it’s DNA.

I am spending so much time talking about this adaptation’s context, because in short the film is dire. What do we lose when we photocopy the imagery of the past, but never meet the reality of those locations, of those places? When we rip the ideas, the evocations of a Weimar Germany, filled with pre WWII dissension and ambitions, and use them as a collage board to paste what we think is interesting now? We have the rush of modernity literally pasted onto the imagery of the past to try to infuse it with the past’s grandeur.

Life is so fleeting, and the sheer will of trying to evoke the past in this film becomes more significant as an act of ambition, than it does provide any meaningful results. Doug Jones’s performance of Count Orlok deserves praise, as it signifies the gap between those who pay vestige trace to the past and those who get lost in trying to replicate it. Jones has some of Kinski’s obsessive desire to mimic and replicate the horrifying impression of Count Orlok, but it is submerged under an awful cut and paste of American filmmaking conventions, of the Gothic made mundane. Characters speak in modern vernacular, with modern tics and behaviours, and it creates this bizarre separation of the two worlds. Dialogue is risible, written like it is fancy dress, a costume for halloween, a memory to be worn for entertainment.

Here is Nosferatu as just an image, an evocation of what someone who loves Nosferatu feels like. It is a project which cannot escape the grasp of the original’s shadow, because it shines no light on the subject. It is like a haunted house ghost ride, a retread of the same story with paid actors who all look like they go home at the end of the day. It is a fan rollercoaster, an amateur production put on in a small theater simply to just bring the story to those who might not know it, but at the expense of completely dissolving the spell the story has woven or where it came from. It is Nosferatu in a green screen parking lot, where one castle might live alongside one spaceship alongside one sunny hillscape alongside anything a computer might replicate.

The difference in places previous, is that the authentic replication of sets and matte painting allowed for a fusion of imagination and reality. The sets in The Wizard of Oz (Dir. Victor Fleming, 1939), in their technicolour madness, present what the world looks like in a phantasmagorica which only works when your imagination sets to work. You can see the draw distance, only guess as to how far the Emerald city may be. But when you literally use the frames of the past, literally use a castle filmed somewhere else, there is no need to do that work. All you can focus on is the distance between the past, and those who painfully try to imitate it literally, and not the imitation of it’s spirit.

Nosferatu (2024, Dir. Robert Eggers)

The end of the year has come and gone now, and I have finally seen the Nosferatu (2024, Dir. Robert Eggers). In the time that passed over this cold, dark winter, I read Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and even found time to watch the 1992 adaptation, Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992, Dir. Francis Ford Coppola). At this point I am soaked in the gothic dread of Nosferatu, the lurk of the night hunter, the pale flesh of those who depend on blood for life. The overwhelming night is a consuming entity in this wintry January. And like a nightwalker crawling slowly out of the tomb, I dragged my eyes to feast.

But the blood is rancid, and the taste sour. On the surface, the appearance of it’s flesh looks appetising. The cinematography, moody and lush with evocative blues, hues of yellow. The framing of winter, mountains and ruined castles and the snow falling in light flurries. The buildings, the dress, the moderate sense of place, decorum and candlelit succour; it contrasts heavily with the presence of monstrosity, of an animalistic hunt for blood. The mood is present, omnipresent and suffocating actually. From beginning to end it seems ready to ratchet the dread up to eleven and never come down. After nearly one-hundred and thirty years in the limelight, the meek, naive expectation of Jonathan Harker’s eerie approach to castle Dracula won’t cut it anymore. We all know who Dracula is, what Dracula is, before we’ve sat down.

So the innocence of the story is killed, and so too much of the innocence of the characters. Everything is soaked in oily dread here, to the point that it smothers much of the nuance and intelligence and dare I say the genuine humanity, of much of the source material (either the book or the previous Nosferatu films). Everything starts and ends with a knowing nudge to the audience, the sheer lunacy of going anywhere near a place called Transylvania, right?

It shows just how much has been lost in translation in this long stretch of time. At the source’s fountain, a range of character intelligences, who believe in the scientific acclaim and rationality of man spend time coming to terms with the possibilities of the dark; the occult. A current of action and vicious events pull them closer together, as they uncover a mystery piece by piece, journal entry by journal entry. Their brilliant minds shine in both daylight and nighttime, and it is with each uncertain, tentative step into the realms of mystery that they realise how uncertain things can really be. In the late Victorian Period of London, on the cusp of a new century, reason and occultism intertwined in a spectral dance.

Now, the characters seem to be pulled and stretched like taffy, to each represent a single viewpoint; almost dissected from each other to artificially provide a conflict between science and occultism. Friedrich, played by Aaron Taylor-Johnson, spends much of the film simply repeating his belief in science, ergo none of the events taking place cannot be possible. Dr Albin Eberhart Von Franz, the occultist doctor played by Willem Dafoe, is his foil. One says yes, the other says no. The nuance and range of beliefs has been narrowed into a tennis match, instead of a complex interlinking chain between characters that is pulled in one way and then the next. Ellen Hutter, played by Lily Rose-Depp, practically cannot stop repeating herself as to the continued persistence of the nightmare of Orlok, regardless of who or how she is speaking to anyone. Herr Knock is slavering, raving lunatic in a performance which sieves through all of the nuance of that original madman; sometimes erudite as a philosopher, other times simpering as a child. It seems to be too much to ask reason and occultism to dance here, now it is a sport; only won or lost.

The historical fastidiousness is there; Eggers used a reconstructed Dacian language (it’s source found in Romania, home of Vlad the Impaler and influence for the vampiric antagonist) for Count Orlok to speak. In his words there even contains the essence of those conversations and elucidations on the spirit of monster and man. It is just the human characters, who populate most of the run time of the film, who fall into a depresing sort of modern address; the ways and the manners of which they speak to each other more reminiscent of modern conversations than those in the film’s setting, 1838. Foreign customs are simply looked at, made to seem uncanny and unnatural, with no real sympathy or empathy to the portrayal of the Sgzany gypsies. In fact this film probably has one of the most unflattering portrayals of them, in a bizarre ritual dream where one of them is riding a horse naked.

So much of the subtext, the implications of what the intellectual conversations previously contained in this story, has been made literally textual, baring it’s insides in a grotesque display of trying to mimic the past as the characters address each other in ways alien to that past. Cinema has truly wrestled the literary nature of the story to the ground at this point; fangs bared, ready to drain its’ corpse.

If this sounds convoluted and complex, perhaps. It lies in the ways characters confront each other, talk to each other, that feels more reminiscient of American high schoolers putting on an English play. The words are there, even the accents and affected postures, but it feels like the characters do not really know why they are saying these things. Maybe the language is too clipped, too functional; lacking the floral elegance of the original’s Victorian English, or the forceful natural spirit of the German filmmakers lingua franca. To mine so much dread, at such a consistently high level and high temperature as the film does, you lose a sense of elegance; of the spiral into the insanity of the situation unfolding right before your eyes. Instead conversations become more blandly functional, scenes of hysteria seem designed only to keep the fire high. Character’s traits and ideals are as wishy-washy as the plot rollercoaster demands of them.

I wish Robert Eggers well, he makes films at a really high level and seems to be enjoying great success in the film world. He has a keen interest in those subjects of gothic nightmares that help keep cinema a little different; not just an endless stream of popcorn stuffed into the eyes and mouth (I am big fan of popcorn so I don’t want this to come across as disrespect for the food or the cinema genre, they have to stay in operation somehow). I just can’t pretend that I love these works, his love for Nosferatu is clearly self-evident. He made the film as a play back in high school long before his cinematic career took off, he clearly has a deep dedication to the fable and the myth and the hunt for satiating a vampiric appetite for blood.

It just might be that he is the victim of a darkness far worse than a vampire; a darkness of numbing, well produced remakes that only circle the striking spirit of the original material they are based on.

-Alex

Leave a comment