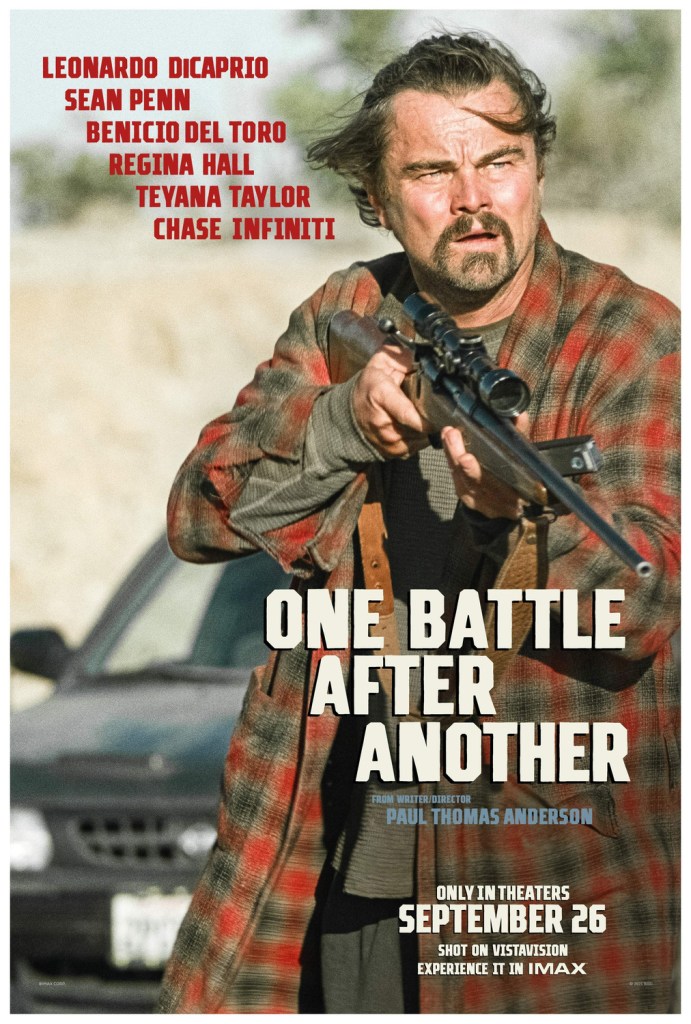

He’s back.

Cinema’s greatest wunderkind Paul Thomas Anderson brings us into a world filled with paranoia, politics and power. Family structures collide with towers of social inferno, grinding the souls of America into fine sand.

Keep your head down out here, there’s crazies on the loose. And you’re too old and tired to maintain their pace. Still, you can show them that an old dog knows a few tricks. That passing the torch to a newer generation can still be done with style and flair.

It’s a little long; a little baggy, full of soft dozey visual fireworks that keep the film lit up with visual panache; it’s colour palette and gorgeous range showing up just great on VistaVision. I felt like I had to really look/pay attention to understand it’s full range (mini explanation here), but I was sat way up, residing in the nosebleeds. The widescreen compositions give a beautiful depth to the horizontal, parallel stories, narratives criss-crossing and zig-zagging across the screen. Lives brew, steam and bleed unevenly through character histories. Atoms of manic personality smash through a rollercoaster of events, happenings, u-turns, loop-de-loops and spirals of characters spewing forth life. Everyone is along for the ride here, all the miscreants, rock crawlers, night stragglers, every quiet and mispoken figurant lurking in the murky background. Someone’s come along with a flashlight, lighting them all up with shine, a smile, and underneath it all a paranoid glare.

Comparing it with Eddington (2025, Dir. Ari Aster), I’m impressed with the use of richer, more elliptical and subtle storytelling to evoke richer emotional truths from the surface fat bubbling away in America’s modern context. Eddington is a snapshot of America’s boiling, roiling toxic surface, the subtext bursting and morphing right into the text. One Battle After Another is able to deftly maneuvre into more ambigious territory, because it sacrifices an ‘omniscient style’ overview of society’s crevices to hone in on a specific hue, a specific perspective carved out of left-wing rebellion, stonerism and paranoia. We are shuttled along the lives of the participants, along narratives which seem to be chasing each other down like wayward rabid dogs.

The Battle of Algiers (1966, Dir. Gilles Pontecorvo) being such a touchstone for the piece is quite interesting. America’s cinematic history is rich and varied in ways few national cinema’s have ever had the opportunity to portray, but a muted disquiet follows its’ history on cinematic liberation politics. Following WWII, and the dismantling of much of colonial rule across the rest of the world in the following decades, a politically fractious and explosive history of films follows in the wake across Europe, Africa, Asia and South America. A history of increasing visual literacy, access to visual equipment, innovation in methods of shooting/narrative styles. The characterisation of the populace in The Battle of Algiers is one of the most multifaceted representations of a populace at war with itself.

So PTA has conjured up a sort of The Big Lebowski (1998, Dir. The Coen Brothers) styled addition to the canon, a Zanuck brothers style comedy of guerilla warfare. Which is smart, because it almost seems so goofy that at times you forget it never quite backs down from its’ own rebelliousness positioning. Rather than maintain an arbitrary sense of objectiveness in portraying modern times, we sink into a well of analog characters, deliberately at odds with the digital sanitisation of our times.

We live in a time of documentation,documentality, everything constantly recorded, monitored and catalogued; all able to be retrieved in high-definition preservation. Anything that falls outside of those categories as we see, is at risk of getting into a shirty phone-call concerning the fact “maybe you should have studied the rebellion textbook more closely”. It is a poignant reminder of just how scrappy our collective junkyards are. How the architecture of even the shadowiest figures is a bolted together mongrel of ideals, degenerating technology, and cracked codes of loyalty, secrecy and once again, paranoia.

Gabriel Garcia Marquez, in his Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech said “our crucial problem has been a lack of conventional means to render our lives believable. This my friends, is the crux of our solitude.” A lot of the reason why it is hard to tell stories about the unknowns, the hiddens, the underneaths, is that their stories are invisible. They are trying to hide. Any exposure is potentially life threatening. So telling a story about those concepts; hiding, invisibility, almost living underneath society due to fear of discovery, by touching on all these in more abstracted ways it can create something less forceful than choosing a side.

It creates understanding, sympathy if you care for it too. PTA’s film touches on causes it empathises with; Black Liberation, the Gen Z gender movement,the current status of migrants from Latin America, but it isn’t interested in assuming the grand role of moral arbiter. It steps in and out of the rivers as it’s characters barrel out of the solitudes which have locked up their hearts. It’s a neat little magic trick, like watching a pinball move so fast you can’t see the score racking up.

When you displace yourself from trying to cover the whole portrait of society, you risk more of your own attitude appearing on screen. PTA’s characters stumble, trip, step, they even fall down a 40ft tree at one point. Who’s to say the revolution wasn’t silly, that it wasn’t just a disorganised coalition of actors in both good and bad faith scattering to the winds of time? It’s a rather fresh approach, and one that can slide a little easier under the radar of our current, rage-filled times. Sugar sweetens the blow, and the zen established by performances in Chase Infinti as Willa, Teyana Taylor as Perfidia Beverly Hills, or Benicio Del Toro as Sensei Sergio St. Carlos just help blow the film out of the waters that others have been splashing around in recently trying to make films about modern America.

Films are an alternative medium to capturing the ephemera of life than say ‘the news’ or ‘history books’. Not like the hard bold headlines of newspapers trying to define history, films act like butterfly nets, capturing the shimmering of life in motion, temporarily. A fictional history evokes a deeper, more resonant perspective in this case. Flights of fancy take flight inside the text of a film; like a glass display case for dreams. A reality, a truth persists in a film, but who’s to say, and to what end? What if your life gets upended suddenly, and everything changes, becomes new, the most integral and important moment being continuously Now right now, as you’re on the run, looking for your daughter. The fog of history meeting the mist of futures in a churning landscape disentegrating around your very eyes.

Films offer counter narratives often because humans have a tendency to hide information that makes them look bad. So it’s nice to see a film which feels like uncovering a rock and watching the wildlife scuttle out from underneath. After all, what right do you have to separate yourself from them? They crave shelter from the storm just the same as you.

That’s all for now.

-Alex

Leave a comment