///

To understand what’s happened at Woodstock, it’s important to look at what came after, what came before.

///

Gimme Shelter (1970, Dirs. Albert & David Maylses and Charlotte Zwerin) is a look at the festival which dealt a death blow to the spirit of the Sixties, only months after Woodstock ’69. The Rolling Stones are shown in their total fuck up of the infamous Altamont Speedway free gig, where violence and rioting led in part to the death of Meredith Hunter, a black man involved in an altercation with the Hell’s Angels (who were providing security to the event). Jerry Garcia’s (Grateful Dead band leader) face drops when he learns that Jefferson Airplane’s lead guitarist got knocked out, which is a sight to behold.

It is heavily laced with the implications of the recklessness and drug-corrupted spirit of Rock & Roll superstars at the time. Mick Jagger’s face is reflected back through the lens as he watches the footage on camera of the fan being stabbed. His bare void of expression, as he struggles to accept the reality of what happened. It’s a hard film to stand in front of, the live footage of a crowd in chaos nauseating as the Stones and other groups try to keep the crowd under control. Everyone is fired out, exhausting their cylinders between intensive tour schedules and drug addictions; it’s a sad vision balanced with earlier interesting footage of them touring the US. Still as much of a firecracker, to this day.

Monterey Pop (1968, Dir D.A Pennebaker) is a welcome step back in time, almost ironic that I saw these festivals in this order. Woodstock (1970, Dir. Michael Wadleigh) is a film defining a generation of teenage idealism, but Monterey Pop lays down the foundations of musicians who performed there. Janis Joplin, The Who, Jimi Hendrix and more got a lot of exposure from the festival, organised by John Dorris of The Mamas and The Papas, alongside festival producer Lou Adler and more. The focus here is ultimately what drives the movement of people to Bethel, N.Y; the performers who play their instruments to others. This footage is about the San Fransisco community who grew a lot of this movement. People who spoke with their instruments & voices, with more verve and feeling than some people do in their entire lives. All their tools and words. It had a performance which made me spontaneously cry in joy,

///

There’s been a lot to think about since starting this Woodstock project. My expanse, the horizons of what I’ve been looking at, are much wider now. Moving beyond Woodstock, has allowed me to notice the reverberations the festival sent out across the American musical landscape.

For all the ink spilled on Woodstock its’ cultural impact was not infinite, and certainly not indefinite. The unique confluence of events which had led the festival; the performers, the documentary and more into a state of celebrated existence, was still just a drop in the cultural ocean. With rock music’s major debt to rhythm & blues, soul music and more, it’s important to note the impact (or lack thereof) on the African-American community at the time of the festival, and also the attempt to create their own Woodstock-type event 7 years later in Watts LA, That’s first, in WattStax (1973, Dir. Mel Stuart), but not chronologically first. Summer of Soul documents the Harlem Cultural Festival happening months before Woodstock (June 29th – August 24th 1969). Hundreds of thousands of black people turn up to see some of the most ecclectic artists of all time. Sly & The Family Stone had to have the Black Panthers do security for his gig because the NYPD refused to provide security because the expectation for the show was expected to be too crazy.

Ahmir ‘Questlove’ Thompson dives into the Harlem Cultural Festival, reflecting how music as a whole is developing at the time, Sly & The Family Stone is maybe the only act who crossed both festivals. Here was my first experience last year with concert filmmaking, and the film does a tremendous amount of grace in restoring a piece of neglected history. The film does work to make its’ history appear more ‘lost’ than in reality, but filmmakers do what they need to make a convincing cinematic experience. Woodstock manipulates its’ chronology, and it can be important to recognise the power of singing as a performance first and foremost. Music can cross so many boundaries, and the organisation of these radically free festivals pre walkie talkie set ups, just organising by hand and voice and power. It can be hard to quantify that.

WattStax is a direct from the old testament style of American 70s new wave recording, of the Stax records free concert. Two years after Altamont obliterates the white hippie movement, Mel Stuart puts onscreen Reverend Jesse Jackson who performs one of the most powerful speeches in cinema history. The music here is distinctly 70s, tickets at one dollar each for an incredible array of talent. When people storm the field to dance to Rufus Thomas’s ‘Funky Chicken’, its’ excitement and freedom is stacked alongside The Emotions gospel performance of ‘Peace Be Still’ which is genuinely soul-wrenching; people having metaphysical convulsions in the church. It’s a beautiful if uneven portrait of soul in America at the time, still alive with passion as Isaac Hayes mounts the stage in a gold chain vest (with the drip) performing soul classics that roar across the sky in fire.

Richard Pryor narrates a long walk through the black experience that ducks and weaves between topics with searing fierceness, his intricate comedy maybe softer now, but at the time must have really exposed people to the black lens, the black vision. Power, unity. WattStax is an expression of that, “I Am, Somebody”.

///

–[On A Film About Jimi Hendrix] “The reason Warner Bros. made the film,” Boyd said, “was because of the record company, because Mo Ostin [chairman of the board of WB Records] was in favor of the project. But Warner Bros. films didn’t interfere or censor the film in any way, and when the film opened at the UA Westwood they were stunned by the business.” (It set a house record, $46,000 in two weeks.)

-Hendrix plays Delta blues for sure – only the Delta may have been on Mars.

Tony Glover, Rolling Stone

///

Documents. I’m thinking a lot about documents, documentaries. I’ve seen a lot of films now in search of Woodstock ideals; exploring multiple musicians and alternative festivals. I’m tired of watching endless processions of sonic experimentation, mass gatherings, artistic synthesising. I’ve been on a solid tear watching film after film, and I’ll try sum up what I’ve seen so far.

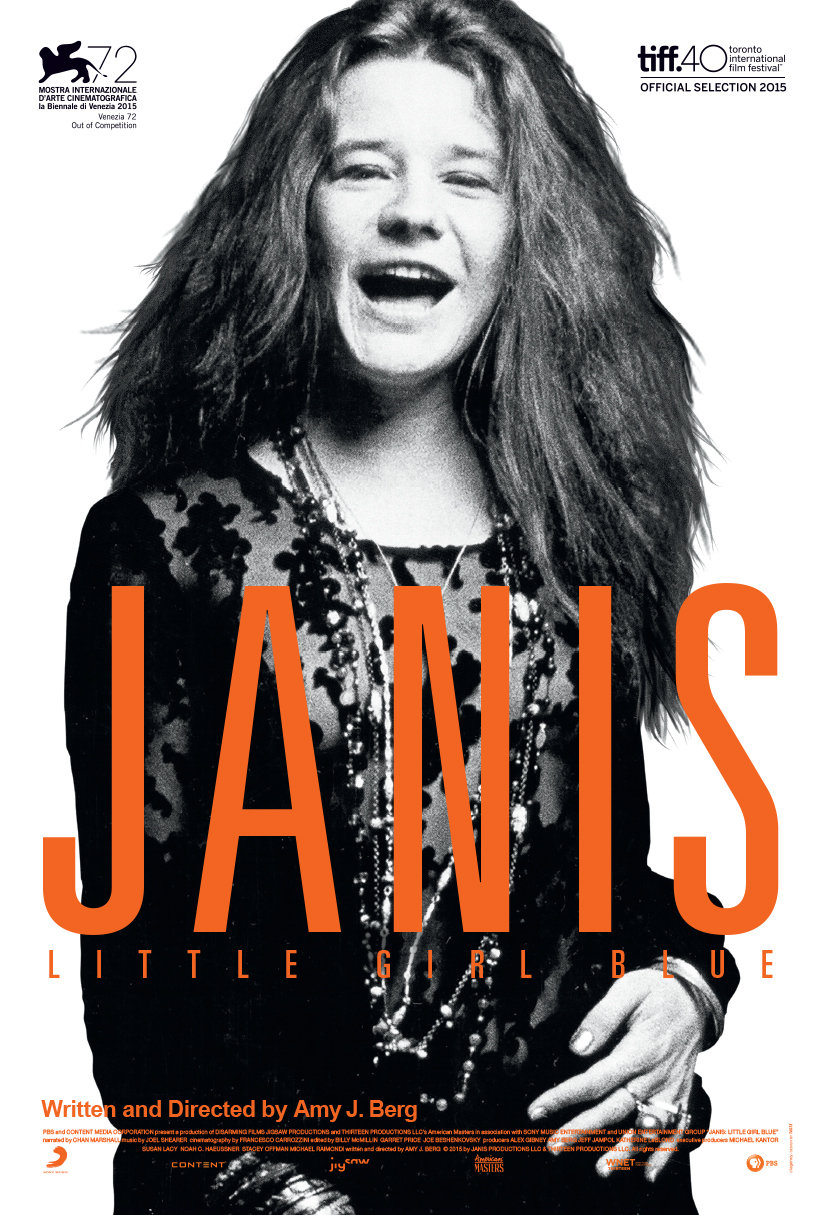

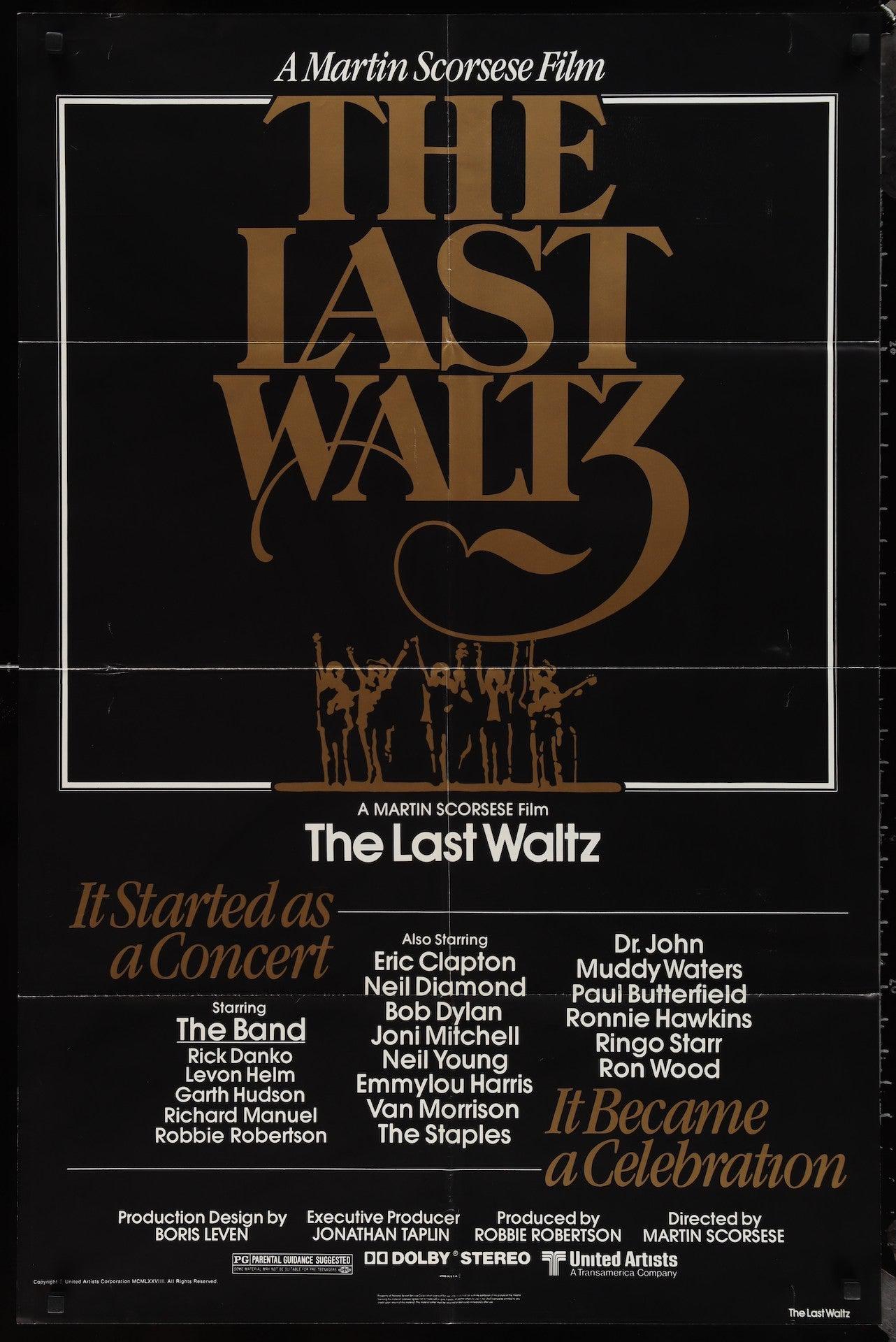

The Last Waltz (1978, Dir. Martin Scorcese), Janis Joplin: Little Girl Blue (2015, Dir. Amy Berg) & A Film About Jimi Hendrix (1973, Dirs. Joe Boyd, John Head and Gary Weis) were the first three documentaries. Here I started at the end, with The Band‘s final farewell performance in 1973, directed by Martin Scorcese (Woodstock editing alumni now risen) expressing how everyone at the time is saying farewell to the ideals of the Woodstock generation. Althought the concert is self-congratulatory, a lot of it is earned in how real the music is, symphonies of rock n’ roll and and a whole artistic tribe onstage.

Janis Joplin: Little Girl Blue is a American modernist documentary, archival footage mixed with talking heads on her artistry The interviews are the main thing I remember from it, a particularly shocking sequence where Janis was voted ‘Ugliest Man’ in her university town/fraternity society,near ruining her self confidence of painful note. Footage of her before her untimely end is particularly harrowing, but each time she’s on screen she’s a vision of a beautiful talent. Still it’s a tapestry of powerful material about her.

A Film About Jimi Hendrix is a different beast, gentle interviews with the people who knew Jimi closely shortly after he died. Although Noel Redding (1/3 of The Jimi Hendrix Experience, his defining band), refused to be interviewed for the film for moral reasons (quoted in the article above), it is a nonetheless frighteningly frank conversation with the people around him who supported his rise to fame and witnessed him fall off the side of a cliff. Performances, wild.

The original Rolling Stone article declared that Woodstock was never actually officially declared a ‘disaster area’ by N.Y Governor Rockefeller, and it made me think about the disaster areas left in the wake of these positive, successful artistic expressions.

///

These direct accounts from Woodstock are filled with positive recollections of the mud, the swamp of the environment. These films do wonders in expressing the collective mud of the counterculture at the time, detailing various Woodstock-era projects and festivals. Jimi Hendrix: Electric Church (2015, Dir. John McDermott) hits the Atlanta Pop Festival, where Jimi played in front of 500,000 Americans in a performance which is maybe the best I’ve ever seen of his, even if it doesn’t have the raw power of his Woodstock set. Watching this and Janis (1974, Dir. Howard Alk) was like watching two virtuosos endlessly explore their own inner rhythms and patterns; Jimi a master of guitar and Janis a master of voice.

But first, Festival Express (2003, Dirs. Bob Smeaton & Frank Cvitanovich), a record of the Canadian train tour across Toronto, Calagary, Winnipeg and other cities, weeks onboard of musicians jamming together in a ultimately unprofitable venture. Alongside the Avandáro festival in Mexico in 1971 and other Latin American festivals, Electric Church and Festival Express chronicle musical and tribal explorations into the wider cultural landscape, physically as the music traveled to different parts of the continent. Canadian students protested and rioted that the concerts should be free, causing panic and low attendance at the stadiums where musicians were scheduled to perform. Jerry Garcia sets up a free stage to get 6,000 protestors off the of the venue in a move which ultimately reflects bravely but sadly on a world now filled with extortionate ticket prices.

There’s performances on the train from Rick Danko (of The Band), Garcia and co., Joplin, Buddy Guy, even Woodstock bizarros Sha Na Na come back for a brief appearance, their appearance like an odd relic on the horizon of rock n roll’s decline from the top of the sun. Janis then, is such a deep return to that sun setting, as Hendrix’s ‘Electric Church‘ was quietened upon his death. Janis Joplin would die only weeks after her appearance on the Festival Express tour, all the films beginning to reflect off each other in delicate ways like that. Electric Church compares Atlanta to being maybe even bigger than Woodstock, while at the end of Festival Express someone declares it better than Woodstock due to being able to jam with the musicians for so long.

Still even Janis, filled with absolutely touching moments of footage only captured when she was alive (giving the film a mysterious presence of vitality) returns to Woodstock. Performance footage I’ve never seen before of ‘Can’t Turn You Loose’ is again crazy, actually enhanced by the context provided by Amy Berg’s later documentary referenced above. Janis here is on full display in her ability to carry the weight of her own pain, alongside the demonstrated talent and recklessness that accompanied being a rockstar. The footage collected is searing enough to understand why it’s a base for all other future Joplin-related material.

It’s honestly quite amusing that Ayn Rand gave a lecture about how the Woodstock generation represented the end of the ‘Dionysian’ spectrum of infantile passivity and madness. In positing the Space Race gathering of over a million, self sufficient families and spectators in witnessing an extreme achievement of supposed ‘rational thinking’, I feel she misses several key details. Already amusingly touched upon in Summer of Soul, the Moon Landing represented very little to poorer underfunded communities on the ground. Also, that this rational pursuit of lunar exploration and search for exterior space, reflects back across the counterculture’s collective need for interior space, psychedelic space.

///

This has taken a long time, to get here. My final part of this Volume is dedicated to artists who impacted and were impacted by Woodstock, the final pieces in a puzzle in understanding the culture of the Sixties. Bob Dylan, captured here in glittering impact in Don’t Look Back (1967, Dir. D.A Pennebaker) is then explored by now artistic savant Martin Scorcese in No Direction Home (2005, Dir. Scorcese).

Meanwhile, The Grateful Dead Movie (1977, Dir. Jerry Garcia & Leon Gast) is Garcia’s own mixed attempt at capturing The Dead‘s cult-like vision in producing a touring, travelling musical circus and spiritual sanctuary, for decades. Long Strange Trip (2017, Dir. Amir Bar-Lev ((with Exec. Producers Scorcese & Justin Kreutzmann, son of Mickey Hart & The Grateful Dead filmmaker)) chronicles that psychedelic vision across the seas of time, as the band contended with fame, rampant drug use, cult-esque worship, and a continuing back and forth with musics’ pre-established rules and distribution methods. Bob Dylan has catalogs of bootleg material to his name, even creating the first ‘gold standard’ in bootleg material. The Grateful Dead on the other hand, revolutionised broadcasting material when countless fans recorded live performances, cheaply copied and distributed them in local areas to an ever increasing number of fans, trading recordings like Pokemon cards.

///

Dylan makes me restless. The whole processing of writing about him seems like a fool’s errand, because of how connected he is to his art being whatever it can be in the moment. Dont Look Back (deliberately spelt without apostrophe) is a erudite, cinema-vérité styled embarking on a career beginning to get distorted by mass fame and recognition. The film is his tour, his endless becoming as an artist performing to crowds who are just desperate to listen. It is a work which connects Pennebaker indefinitely to the music scene, for good reason.

No Direction Home is more alive for me, if only because of how great the scope is. Scorcese clears through the direction of a man who’s presence was continually expected of at Woodstock, his ghost lurking over the whole show as people thought this mythic presence would come to play. His son was in hospital at the time of Woodstock, but Scorcese’s scorching documentary about this 1961-1966 folk/rock and roll hybrid run, and the presence behind lyrics which are blessed with grace and unfolding is fantastic. Here the whole career of a man who not only mastered instruments, but positively expanding new genres with almost lacksidaisical focus is a true mystery. His lyrics just sculpt around a moment, and the film crashes through audience’s booing, people desperately trying to understand him, pull him towards a political path he seems relatively uninterested in pursuing.

I don’t know what that means for artists, other than his path is his own. And the melodies, textures and refusal to conform to any shape other than what’s required of the moment is really critical for being a great artist, to write a song such as ‘Like A Rolling Stone’.

///

The Grateful Dead Movie is where things get heavier, because The Dead, ghoulish and playful as they are, weren’t the haunting presence at Woodstock that Bob Dylan was. They actually played the original festival, in a set which both electrocuted them and put the audience to sleep with a 50 minute version of one of their songs late into Saturday/Sunday early morning. Bob Weir said that they spent 20 years making up for their poor performance at Woodstock, and their lost performance (existing in partial video footage) is a sad reminder of what can happen when you miss an opportunity to be embraced by those paying attention. Mutliple fans and commenters however refer to the band’s own journey which took them taking a sort of ‘portable Woodstock‘ to towns and cities for decades after, which is a presence and burden that Dylan deliberately tried to shrug off. Here, is Garcia’s vision for their last performances in 1974, or so they thought.

Opening with an animation sequence which supposedly cost half the entire rest of the movie, the film is a surrealist surfboard through the interior of Garcia’s music tribe, a minimal amount of interview material is made up for with images of the Statue of Liberty in the zany acid-soaked apocalypse, before moving onto endless scenes of deeply tranced-out audience members. The film has some really disorienting and hallucinatory nitrous scenes, fans in their own universe in the interior of the venue, not even near the stage. Some great performances, some annoying endless performances (a lot of patience is needed or being completely tripped out helps appreciate the finer points of their psychedelia way of playing). I like them though, and the film is a heart-warming tribute to an artistic project which at the time had built from a phenomenal small district success in Haight-Ashbury 1967 up to then 74-77, during the 3 years of challengable production which split the band in various ways during hiatus (they ended up performing again by the time the film came out).

///

Oh, the guy selling hot-dogs who loves Sha Na Na and thinks The Grateful Dead are too loud, love him what a guy.

///

Long Strange Trip then, is a final cavernous account of the success, but sometimes demoralising weight of the entire Grateful Dead project. Over nearly 4 hours, the film lays out in often thorough detail the ins and outs of an artistic project which survived long after Woodstock Nation generation had return back to humble mortal reality. The Dead were on a reckless fun spree with abandon for years in a peace project of art, music, and mind expansion. After doing The Acid Tests across America with Ken Kesey and just performing for trippers at random, their band philosophy became like that of fingers all connected to a hand, each performing individually but connected at the core. This led to a revolutionary approach to touring musichood and stardom, not as a famous edited performer group repeating the same identical melodies; but as a continually evolving, continually growing, continually changing live touring peformative entity.

This then carries the project into the scope of music’s technological revolution, as 10-15 years after both Janis Joplin & Jimi Hendrix have passed away, The Dead are riding the wave of bootleggers trading their tapes at the height of their popularity during 1984-90, as Reagan clamps down on the free festival spirit which birthed and sustained many of these movements. It is sad to see their success clamour for more, endlessly more, and how the band had to keep giving into that momentum. They refused to play Altamont after the reports of the violence, but by the 80s & 90s reports of violence, deaths and unruly followers had begun to marr the entire spirit of the red and blue skull. The Wall of Sound’s history is chronicled in detail, postively exploring at times how the band could be at the forefront of sonic experimentation as artists. They hired The Rolling Stones previous manager, a British fellow by the name of Sam who cuts through the bullshit of the hippie cult with reckless aplomb. Jaggedly successful, but held back by certain leaderless qualities of the entire group.

Because The Dead, for all their ego-dissolving spiritual roots in the pure pursuit of music, becomes soured by heaven falling from the sky, fans becoming obsessive and inducing reclusive behaviour for the band. Unwanted gigantic crowds, arguments about Hell’s Angels being present and serious drug use begins to soak through the edges of the timeline; the frame. The whole frame of the band begins to sag under the weight of its’ glorious celebration of a communal other-society, draining Warner Bros. (and later their own) financial situation by supporting entire teams of staff and families through the project. They party without talking to each other honestly. Which keeps them tied to the project, for founders Garcia and Pigpen until their painfully sad deaths.

The artistic performances end up near endless, and two things drive the health of members to decline. Ron ‘Pig Pen’ McKernan passes away due to alcohol abuse related conditions in 1973, which is covered in touching detail. Garcia’s passing is ultimately more haunting, his entire presence radiating throughout the entire band’s life like a huge sun of love, he described the band ‘as a little patch of flowers growing in a clearing in the forest’ for God’s sake. The whole project is a much more intense vision of what happened to the Woodstock ideals as the few who did carry a torch genuinely kept it lit. You don’t need to take into account the individual success or failure of any one resonant strain of the band, it was a phenomenon which even for those bizarre hundreds and thousands lifted them out of a kind of mass sleeping even temporarily. The Deadheads are the ultimate fans, proto-religious converts of a wave that wanted to believe in the pure release of expression above all else, in a mandala of people (a deaf section where people listened to the vibrations through balloons and had a sign language interpreter for Jerry’s lyrics, for example).

A really touching moment is when Jerry late in life said to his then wife “I could just live off of the ice cream money you know” (referring to Ben & Jerry’s flavour ‘Cherry Garcia’, released in Feb, 15th 1987). But ‘Death Don’t Have No Mercy’ and he comes for everyone in this land. The last footage of Garcia playing on stage is haunting, a shadowed husk hunched over his guitar performing the echo of a once great noble dream. I’m glad the band managed to be such bizarre countercultural successes, outliving and lasting many of their more famous and more respected peers. Perhaps then this is all there is to say for now, on the Woodstock generation. I feel like I have a much greater understanding of how such a gathering could have manifested, a thorough and ongoing obsession with ruminating on the soul of America, entertainment, and music.

-Alex

Stay tuned for the final Vol. 3, where I’ll bring my understanding up to what happened after the initial festival; the re-occurences, the organised festivals of ’94 & ’99 and the various fiascos that followed, and its’ eventual place in the world now. Alongside some other offcuts.