Our eyes see very little and very badly – so people dreamed up the microscope to let them see invisible phenomena; they invented the telescope…now they have perfected the cinecamera to penetrate more deeply into he visible world, to explore and record visual phenomena so that what is happening now, which will have to be taken account of in the future, is not forgotten.

—Provisional Instructions to Kino-Eye Groups, Dziga Vertov, 1926

Working mainly during the 1920s, Vertov promoted the concept of kino-pravda, or film-truth, through his newsreel series. His driving vision was to capture fragments of actuality which, when organized together, showed a deeper truth which could not be seen with the naked eye.

—Wikipedia Entry on ‘Kino Pravda’

In this series, which will run sporadically and when the material presents itself, I will cover documentaries which eschew the traditional forms of documentary style in favour of a more abstract (but not necessarily poetic) presentation of its subject matter, which seems to speak on a greater level than the sum of its parts.

All sorted?

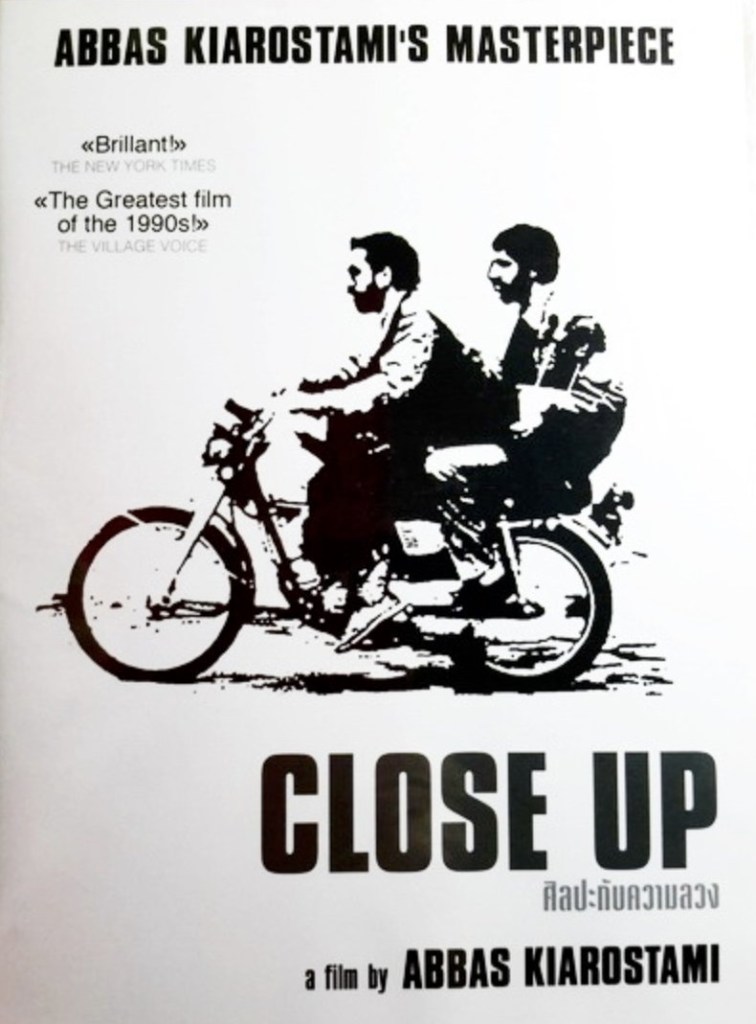

It is very easy at any point to tune out of Close Up (1990, Dir. Abbas Kiarostami) if you so desire. Usually this is a mark against a film’s quality, as it often points towards a lack of necessary engagement needed to enjoy a film work, fiction or otherwise. Something in the design of the film might be constructed in such a way that it doesn’t excite the imagination vividly, the material doesn’t resonate with the human experience convincingly or with enough clarity. What I found in Close Up, was the impulse to tune out of a cinematic experience which seems profoundly anti-cinematic, or rather yet extremely anti-spectacle. The visual representation of space and time found in cinema has found dominant and alternative modes of expression, of visual languages which compete with each other in the cultural clouds which pass over our world. The language of spectacle in cinema has been one of it’s strongest ways of speaking, everything from explosions to sexual appeasement to even the close up itself. Often employed as an exploitative camera move to communicate as much visual information regarding character’s communication cues as possible. Faces are relentlessly seen, studied, given full dominance over the screen as we empathise, understand, align and re-align ourselves in an imaginative world, the spectacle of the human reaction given to the canvas over and over repeatedly.

Kiarostami is not concerned with the language of spectacle, and so it becomes very easy to fall out of it’s gentler, more delicate grip. Spectacle is a language of grabbing your attention, of a screen filled with such visceral reaction provoking cues that you do not need to jump into a film, for the film jumps into you. This has been one of cinema’s most invigorating tools in it’s history, a catalyst for some of its’ most incredible shots, scenes and films. But it also a language which can scream so loud it can simply drown out the other voices around it, not through malice or intention; simply through presence. Perhaps this is a very elegant way of saying that at times, watching Close Up can feel like and can be boring. In a cinema of spectacle, the mundane is often barely worth commenting upon. Nothing more than a quick set up before the extraordinary events begin to occur, the “real” journey begins etc. The mundane in awkward and shabby clothes, stands off to the sides of cinema quietly waiting for a turn which never seems to fully arrive. The fear of boredom is a cultivator for this language, and cinematic constructionists have spent a long time on the run trying to create ever newer, ever more dazzling scenarios to fill audiences with spectacular elation and leave them for lack of a better term; unbored.

Kiarostami cares a lot less about catering to the sense of being entertained. Spectacle is a part in the multi-faceted language of entertainment, but what about cinema whose aims are beyond that of conventional entertainment? The mundane is something very ordinary and therefore not very interesting, but why have we deemed it common law that ordinary things are not interesting? If something is common, we deem it of having little value, praising only the rare as excellent. But what is ordinary is not set in stone, and the language of boredom is one which is shaped by our cultural concerns and perspectives. Cinematic logics can be varied and idiosyncratic, but the language of entertainment is that of the circus; keep the people fed and keep the people happy.

So Kiarostami takes us into a different world; the one much similar to ours. But one of the main differences here between the language of spectacle and the language of the film he builds is that spectacle is often a witness; the camera is a cypher for the witnessing of spectacle, voyeuristic and eyes drawn open but silent. Here the camera is an intervenor, a camera whose existence is central to the entire film. It is complicated to place Close Up in the “Docs” series, because its’ origins are intimately tied to the reality of the events but also the guiding vision of Kiarostami’s imagination. Hossain Sabzian is a man who impersonates Mohsen Makhmalbaf (a famous Iranian director) when meeting a woman on a bus. His lie leads him to a continuing stream of contact with the Ahankhah’s (her family), which culminates in his revealed identity, an arrest and subsuqent legal proceedings. But this is interventionist cinema, and Kiarostami after reading about the story in an article in Sorush magazine met Sabzian, and began to develop a film about these proceedings. After gaining access to film the trial, Kiarostami convinced the participants of the story; accused, accusors, judge, journalist even Makhmalbaf to participate and even recreate scenes around the encounter as it was unfolding. A film whose existence is inexorably tangled into the real life DNA of the story it portrays.

Is Close Up a false documentary, or a true fiction? So often lines we draw to categorise and segment our experiences can’t survive exposure to the elemental powers of cinema and the world. Kiarostami’s involvement in the film is highly visible highly emotional highly subjective. It is not a witness, it is a direct instigator and intervenor of the events itself. In effect, “the film is not one in which documentary is blended with fiction but one in which an intricate fiction is composed of real-life materials”. So why does it land here, in a category concerning documentaries? Well, what is ‘Kino Pravda’ and what is Close Up, if not fragments of actuality which when organised together, show a deeper truth not visible to the naked eye? A witnessing camera must be invisible, it must not draw attention to itself. But like Dziga Vertov in his Man With A Movie Camera (1929), Kiarostami does not need to hide a camera which seeks to be an active part in its’ own construction of a film. In fact with a sense of empathy which stretches into the extraordinary, we are journeying with the camera and its director as they actively try to navigate the course of their own stories as they unfold. The artificialness of their staging or their re-dramatizations is meant to be taken into account as part of the experience, not something that needs to be imaginatively bought into to create entertainment. Like the recreated experiences of those encountered in The Act of Killing (2013, Dir. Joshua Oppenheimer), their positions in their own experiences are highlighted for you to witness, not with the awe of spectacle, but with the bewilderment of considering the fundamental complexities of the human condition.

The mundane will never be the shining glittery jewel of cinema, and never asked to be. But the mundane contains such a world of gentle, intimate and powerful concerns which so often than not dwarf the imagined heights of fancy that our extraordinary counterparts seem to live in. Our lives are filled with the atmosphere of the mundane, the invisible conditions of our everyday visible concerns and issues. And here at this nexus of art, truth, reality, imagination, film, life, suffering, justice, compassion and understanding, stands an extraordinary film. One which reveals fragments of truth about our world. Maybe the truth is boring and needs to be tuned out. Maybe.

Maybe the truth is interesting and it needs to be tuned into.

-Alex

P.S If you liked this please follow us on twitter here for updates. Also we have a DONATE button on the side menu and if you have any change to spare would be greatly appreciated, help us keep writing!