///

These are the highlighted scraps from my Woodstock series concerning the festivals following the original 1969 festival. Celebration events happened in ’79, 89, ’94 and ’99. Some people think that the festival spirit needs to stop, with the final death knell in a cancelled 50th anniversary during 2019. Michael Lang passed away; the Japanese investors just not inspired by the idea. There was also celebrations both at the original site and elsewhere in the wake of Woodstock’s legacy. A ’94 inspired Polish variant for example, drawing just as many if not more people. When Red Hot Chilli Peppers played Hendrix’s ‘Fire’ to a crowd burning the field they did not know it would be the last associated Woodstock performance. Supposedly an All-Star Hendrix tribute band had fallen through, and as ghostly footage of him played over a rioting crowd, Woodstock and the associated images on film were changed forever. So have a read, if you will.

///

Woodstock ’79 – The Missing Files

The Celebration Continues: Woodstock ’79 is a documentary I can’t find. A VHS of the performances at Madison Square Garden, I read that it contains a lot of great jams. There was another concert at Parr Meadows, Woodstock Reunion 1979 where between 18 to 40,000 attended, organised for the 10th anniversary of the festival. Supposedly there are bootlegs of it out there, and the story of Ron Parr is a novel in itself. But the Seventies, the records and reports of the concerts are out there somewhere. In memories, old radio broadcast performances uploaded online and this great performance I found from Canned Heat. It’s history recited here is interesting, staged by the original stage manager John Morris, it’s just a shame that much of its’ intrigue is now lost to time.

///

Just like The Band’s legendary fragments of their performance at Watkins Glen, what’s left is so unique.

///

Woodstock ’89 – International Spectres and more Missing Files

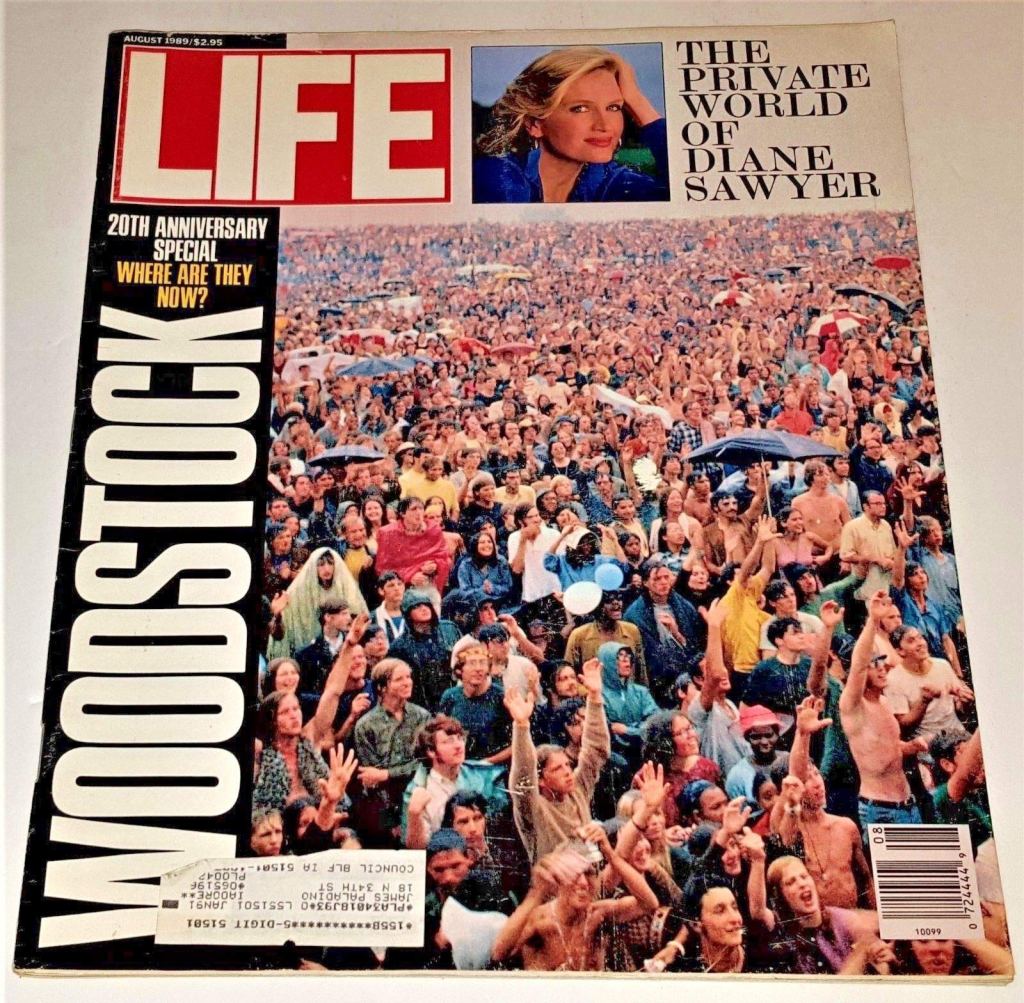

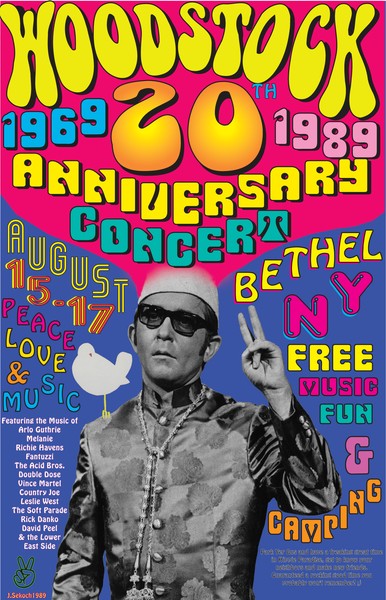

You can see this documentary in German about ’89. Or this news broadcast, or this eerie clip about a news-dubbed ‘Aryan Woodstock‘, a racist concert being organised the same year. Or in old archival audio clips reporting that over 150,000 people passed through the event. Woodstock as an event treads an uneven path to commercialisation, as the excesses of time and legacy begin to surround the event. This is maybe the last time Woodstock is not soaked in corporate entertainment and soft drinks, people bring food and drink and the PA and just set it up, like an inevitable wave crashing over the farmlands.

There’s a Filipino styled event, Pinoy Woodstock which also takes place. Another Canned Heat performance later in the year. And the Moscow Peace Festival, the beginning of the end of the glam-rock insanity. Woodstock is now international, the spirit of festivals as movements. They’re discussed on Oprah. Woodstock here is not the lost, misty drift of the Seventies. It’s caught in video fancams, Jack Hardy’s rendition of ‘The Hunter’ as a total eclipse of the moon happens, Melanie’s continued presence, a full set from a rock band I’ve never heard of called Savoy Brown. The most broad view is this assembled 27 minutes of footage, and it reveals some perspectives, but it seemed that Woodstock’s influence at the time had escaped itself, ‘The Forgotten Woodstock’ being an event overshadowed by the cultural spread of rock n’ roll.

But then reading its’ history and creation, and the unlikely spiralling of the only major event which ever took place on the original site in Bethel, is a wondrous thing. Maybe 40,000 people were in attendance at any one time, but 250,000 passed through they say. The genesis is from the original Woodstock organisers saying they weren’t doing anything to commemorate the anniversary. In fact, according to the stories, the grassroots festival actually got ahead of an officially sanctioned ‘Remember Woodstock’ event at a nearby hotel, with promoters trying to steal fans! More rain, more shenanigans, but with a spirit that seems so fresh and genuine, that it is maybe the last gasp of air before…before Woodstock hit MTV.

It was unbelievable. Somebody wouldn’t believe it. It’s a lie, but it isn’t! We were like the mouse against the lion, and the mouse won! For once, the mouse won. For once.

Richie Pell, organiser of the ’89 Woodstock festival.

They weren’t gonna miss a chance to make money this time.

///

Woodstock ’94: Peace, Love and Pay-Per View

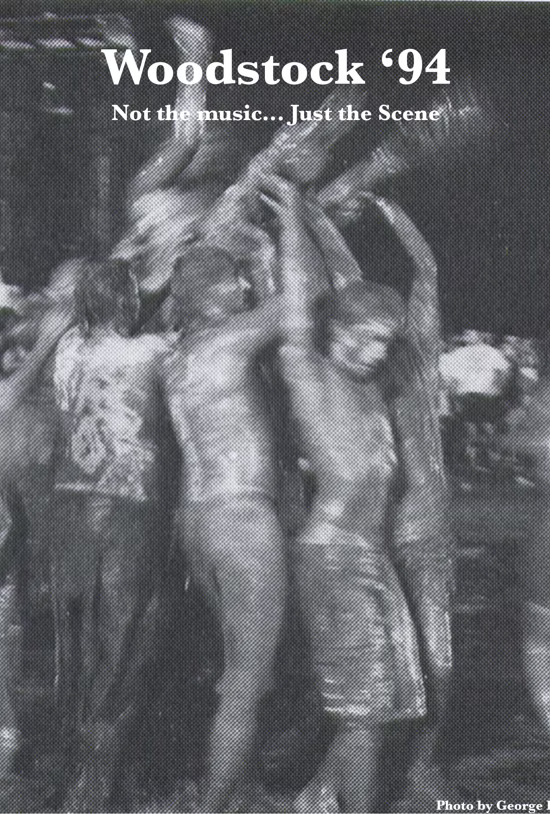

The found footage of the gatherers at Bethel in ’94 is quaint by comparison, with its’ gentle folksy atmosphere. Melanie Safka and Arlo Guthrie make brief appearances, while the couple who get married are delighted by the reception of those with enough sense of memory to have ventured here. Woodstock is a legacy now, and the merits or flaws of any of those attached to the ‘peace and love’ ideals of the Sixties, is about to hit that new media craze: fragmentation. When the tickets cost $135 dollars at Saugerties, Melanie shouting “Welcome to the UN-concert” reflects back the uneven environment that rock music, peaceful ideals, and commercial capitalism clashed together in the Nineties. Polygram gave them $30 million, and then head John Scher (later co-organiser of Woodstock ’99) was gonna make sure this was for the hippies, with big wallets or small.

’94 is a crazy time for Woodstock’s first official revival. A zenith of the Nineties commercial, industrial bloat of the music industry as rock music buckled under the grunge. Post-punk anxiety teens. Hip-hop is in the process of colliding with the festival’s mostly white, American liberal rock bros. The concert is an ironic worshipping of the festival’s original mythologising. Benefitting off of expressing furious cynicism at the hippie counterculture which had birthed the movement. The scene is bursting apart at the seams, sick with music and radical acts wrapped up in Pay Per View, Woodstock Pizza, and branded Pepsi Cans. Kurt Kobain, who with Nirvana had been asked to play, would die weeks later.

///

The Concert/The Documentary – The concert itself; the strong, strung out excesses of rock music at the time. Some of the performances are astonishing, as the rain came down at what was reported as ‘Mudstock’. Nine Inch Nails played their set covered in mud trashing their instruments, Primus incited mud clumps thrown during their thunderous bass set; Green Day got covered in mud so hard they couldn’t play anymore. The scene documented is of a youth teetering on the edge of insanity, washed out and more jagged compared to the counterculture spirit from the first festival.

///

Then again, maybe not. Woodstock ’94…Not the Music…Just the Scene (2017: Dir Tobe Carey) chronicles a world of independent thinkers, caught up in the mess of late Nineties commercialism; where 1994 woodstock wire cutters cost $2.00, and a ticket to the festival $135. Michael Lang, Joel Rosenman, John Roberts, the earlier founders of the first festival are like gentle ghosts in the footage surrounding the festival. Lang’s image was and is still sold in memorabilia. Images I once took more genuinely, now crass and assembly produced by a Woodstock nation living off the dream.

On site at Wood$tock, as critics dubbed the event, Apple and Phillips hosted product demonstrations, while vendors peddled Woodstock dog tags, a $350 Woodstock leather bomber jacket, and the piece de resistance, a Woodstock condom, which retailed for a buck.

Oral History of the ’94 event

///

The MTV footage is where it reveals how big of an event it was, because this isn’t a festival contained in a singular vision; Woodstock via Michael Wadleigh. This festival doesn’t have the the numbers of the original festival, around 250,000 people made their way through the absolute rabid crowds featured on MTV’s PPV coverage (online in archival footage). The presenters; Tabitha, Bill, Juliette (poor Juliette), Chris, Alison, John, Ed, Rick, Kennedy (who went and woke people up at six in the morning in their tents! After partying! MTV was crazy).

People use words like goofy, watch weddings on MTV while other interviewers ask festival participants to eat mud and backflip, others go to the Surreal Fields; the technology center where people can experience the technology of the future! Strange visualisers and wirey technology of the wired generation, it’s imagery is powerful with a modern nostalgia. The computer stations, clunky monitors which project word processing documents, all for the people of Woodstock, sponsored by IBM! There’s a Woodstock Marvel comic tie-in. The American kids who just wanted everything to be punk rock and crazy and shredding! They’re all here at this mud-soaked Americana, it’s fingers just in the darkness.

///

They closed the freeways on this one as well, so many people made the pilgrimage this time around. People made a tremendous amount of money of this one, but it being free meant they lost money. You can see at times the sexist politic of rock at the time come through, Bob Weir of the Grateful Dead reported how weird it was that girls were being ‘molested’ in the crowd, it just has a slightly outrageous anarchic vibe to the whole thing which can be scary and hard to watch at times. Salt N’ Pepa getting interviewed is one of the highlights of footage, but there are relics of the Nineties which cut like glass here. The mud broke heads and ankles, but the culture is a casualty of some of its’ own ideals.

///

It is genuinely anarchic though by modern standards. The festival overwhelmed even the original historic festival which was meant to open in Bethel N.Y, where Richie Havens, Melanie and Country Joe offered to play free, and a crowd of 15,000 strong turned up to camp after low ticket sales cancelled the official event. Fossilising in the cracks, is some of the most fluid evolutionary beats of rock music as it probably entered its’ last major cultural decade (fight me).

///

///

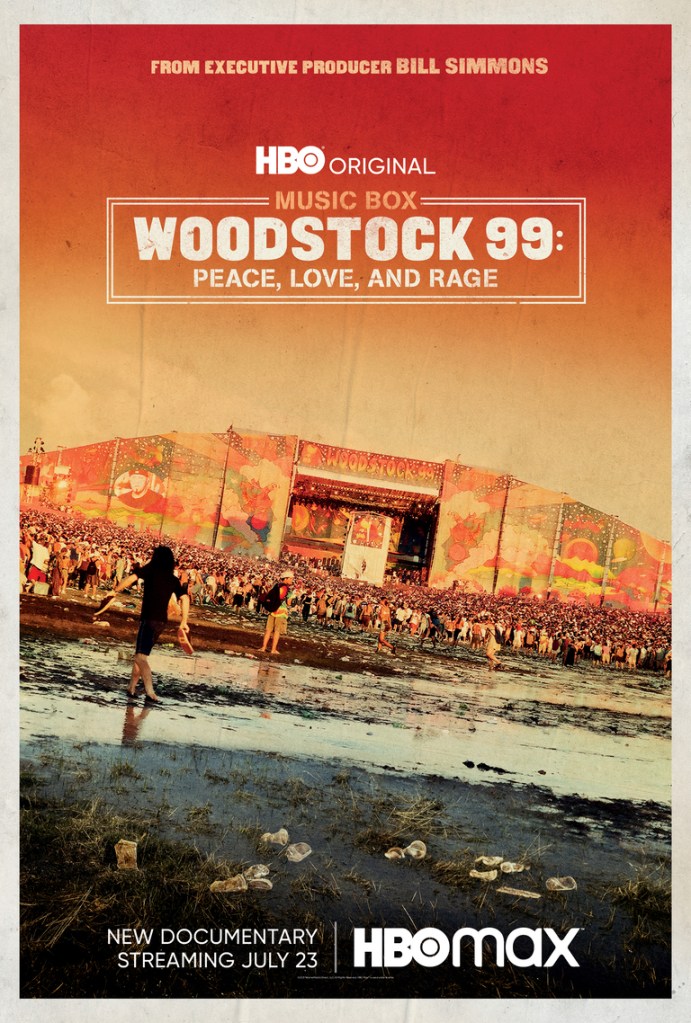

Woodstock ’99: Love is a Nightmare

Woodstock ’99 is like hell. Or heaven, depending on who you were. At the turn of the millenium and Y2K, American youth culture was in an unhinged state of reckless abandon, industry frustration, and the bizarre new genre of nu-metal. Kid Rock and Limp Bizkit are two of the biggest acts, and their sets are such aggravated carnage that if anything, the war had come home to Gen X and the musicians were very pissed off. The future lay in some of these kids hands, and they traded it on for an obscenely overpriced musical cash-in, with rape, riots and a bullet in the image of rock n’ roll for the Nineties . It’s nightmarish, fire fuelled imagery is only the beginning in a saga of clusterfuck events which was this carnival.

///

Woodstock ’99: Peace, Love and Rage (2021, Dir. Garrett Price) is where my journey began, several months ago the flashing release of its’ premiere helped prompt me to begin watching the footage, from the very first film by Wadleigh.

Santana played ’94, but here the viewfinder pointed forward to what Michael Lang and John Scher thought was going to be a visionary success like the first one; but also (and very importantly) making more money than Woodstock II. At a decomissioned military airbase in Rome N.Y (in the blazing July heats), masses of humans started swimming in human piss and shit as portable toilets overflowed with waste across the flat ground.

Here I can start where the ’94 footage left off, in the spectacular value of the found footage genre of film. Someone’s 3 hour odyssey of the event from the lens of a mini DV. After about one hour forty, it all starts to look a little apocalyptic. The hum of the festival sets the atmosphere for a world apart from the rest of humanity.

Every Woodstock seems to have been imbued with a spirit of collective chaos which sort of overwhelms the event, as people gathered in their hundreds of thousands to listen to the sounds of their generation. The original event had a connection to the Vietnam-era protest movement. Anti-war ideals, anti-government ones too. Musical acts, drugs and a commitment to keeping things peaceful. In ’94, once the fences were breached the promoters were largely in the similar position as before: keep the crowd happy and the event will go on. It’s hard for absolutely nothing bad to happen when there’s hundreds of thousands of people around just by statistics.

///

There are stories, the security guard who assaulted John Scher when Aerosmith’s manager was involved in hysterics. The band supposedly sound-checked for an hour, leaving the crowd waiting and fuming. These industry issues, the ‘Peace and Love’ ideals which had so earnestly knitted the previous two events together into strong successes were mocked in ’94, and here five years later they were torn the fuck down.

///

The music, is a unique time capsule of an America resting on change; on Napster and digitalised music consumption. The Nineties had produced ten years of aggressive angst in the American collective, from Nirvana obliterating the industrial faith in record companies taste in 1991, through 94’s genuine breakthroughs of NIN, Green Day, Primus’s set is crazy. There are still too many concessions to mainly white rock n’ roll boys in ’94: Salt n’ Pepa, Arrested Development and Cypress Hill are some different acts, on top of mainly hard white rock (Aerosmith, Metallica, RHCP etc). It was bloated, excessive; lumbering like a Ghibli creation towards its’ home destination. But the spirit of ‘Mudstock’ and the footage I saw really seems like a diamond in the rough of a time. Not exactly ‘Break Stuff’.

///

Limp Bizkit is a pretty crazy phenomenon, the media contreversy surrounding his performance a catalyst for the energy of so much of th rage: the anger just overflowing over the culture as well as the conditions of the festival.

They hated MTV now, the crew actually having to pull out towards the end due to feeling unsafe as the fans no longer warmed to their now sold-out image. They hated being in an overpriced commercialised husk of a festival and they were going to let people know about it. The hippie ideals were up for destruction. Trigger Warning for sensitive issues, cultural depictions of women, rape: This was the era of ‘Girls Gone Wild’, and Woodstock at this point seemed to be amplifying the expectation that women were meant to be free, topless, and objectifiable. Women in the crowds were groped as they sat on shoulders or passed overhead; some women were even reportedly raped at the festival. That some of these events could take place in a crowd during a set with multiple participants or an inability to see/report these ongoings to security, the event seems shocking de-regulated in the occurence of modern day mass attendance festival culture. Lack of security is only compounded by a lack of culture of people not protecting each other.

The fires and general destruction of the event are more in keeping with the events’ roots in protest culture, but the sexual elements really sour the memory in recent culture. It’s a profoundly disturbing facet of the festival’s existence, and John Scher says some awful things in Price’s documentary which reflect the lack of insight the promoters had about their own attendees.

I guess ’99 is just the storm the calm preceeded. No rain and no fair access to water, people riot. It’s hard to see anything more through the flames. The legacy of this event is so fragmented, the footage I’m watching now video essays, clip compiliations the media of the cyber universe Michael Lang predicted we’d live in. Pepsi adverts couldn’t save this one.

///

I’m at the end of the journey. Trainwreck: Woodstock 99 (2022, Dir. Jamie Crawford) is another three hour ride through the brutalities of the festival, and some condemnation with it. It’s a judgemental lambast against the events of the ’99 events. Much of it is justified but some of it so sanctimonious without ever getting to the dark heart of why these people were so enraged. I went looking for answers, but it treads similar ground to Peace, Love & Rage. Michael Lang and John Scher are now villains of a peace movement turned sour, killed by the culture. References to the crew being evacuated as akin to the “The Fall of Hanoi”, is a cold glass of water over the original festival’s genuine anti-Vietnam sentiment. Trigger Warn. Fatboy Slim talking about his scary headlining set in the rave as a truck drove into the crowd, while a girl got sexually assaulted inside the vehicle is one of the toughest acknowledgements of the festival’s graphically poor treatment of women. End of Trigger.

///

I’ve circled around and around on the footage of ’99, and I can’t find anymore answers there. In Message to Love (1970, Dir. Murray Lerner) is one of the archival greats, the self proclaimed “last great event” by festival organiser Ricki Parr. Herding 600,000+ people into an uneasy truce and celebration of the power of music, it’s sad to see the less corrupt threads of festival life, when they were more experimental. Laughable now, the £3 ticket fee to see The Doors (incredible), Jimi Hendrix, Joni Mitchell (getting interrupted by a crazy man and calming the crowd down), John Sebastian (shout out), Miles Davis; The Who even. It’s important to see the cultures exterior from Woodstock.

///

///

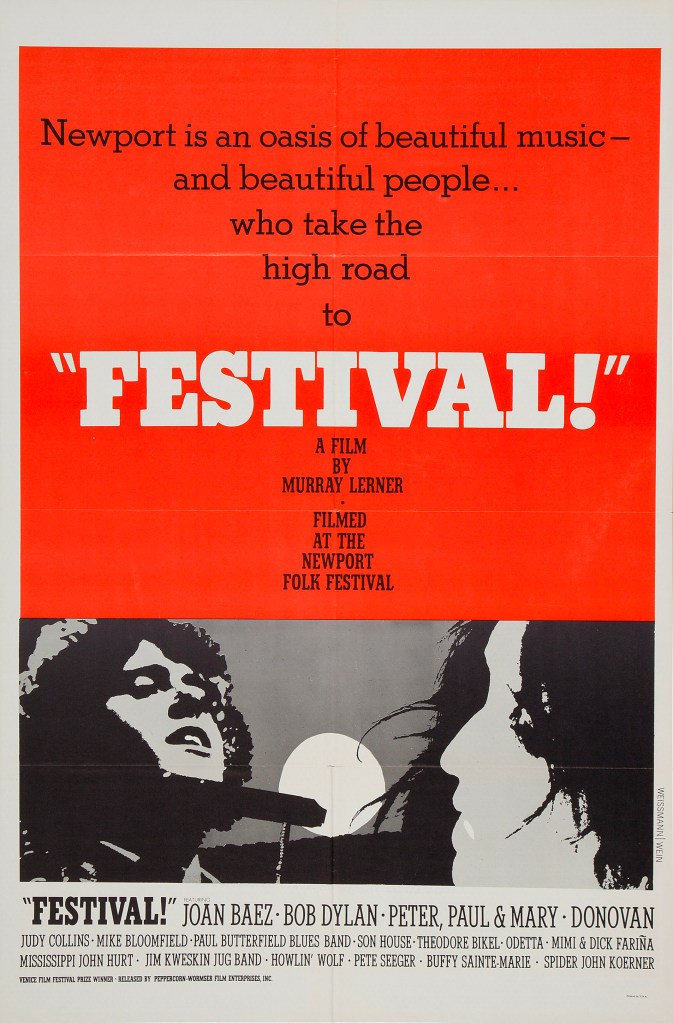

Two portraits emerged alongside this: Festival (1967, Dir. Murray Lerner) and Quadrophenia (1979, Dir. Franc Roddam), ((produced by The Who!)). One, a mirage of beatnik early Sixties culture evolving into blues, as the very spiritual soul of American music (Odetta, Son House, Staples Singers) cavorted with Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Mike Bloomfield. Early modern protest music, a reflection of its’ own times. How could the world be so gentle and so hard?

Quadrophenia takes those reflections and smashes them to smithereens, because the world and teenage culture was violent. Always has been. Mods and Rockers in early 1964 beat each bloody in Brighton, tons of extras; “loads of lads up from Lancashire” just driving down to help out with the film from motorcycle clubs on their scooters. It is a brutal portrait of a disatisfied world, which could just as easily be paired with Babylon (1980, Dir. Franco Rosso and co-written by Martin Stellman of Quadrophenia). The world of music lovers has never been the same as those porcelain, grubby idols who come on stage, dazzle us, and fuck off.

///

European youth culture maybe had a tougher edge than American idealism, but maybe it’s more than that. Maybe America is just too big, Woodstock is only a festival, not salvation. Quadrophenia’s youth riot, riot hard. The making of Quadrophenia memorialises the authentic rage expressed by the extras literally beating each other up to make the scenes convincing. Of course the kids from ’99 were gonna riot, they got screwed over by promoters who booked big bands without even listening to their music. The disconnect between this approach and the original vision is staggering, but it is for other people to judge the distance between those romanticized visions of a Sixties Bacchanalia, to a Nineties Hieronymus Bosch hellscape.

///

This has been a journey, and I am grateful to have seen so many visions of Woodstock. It has been at times exhausting, but always a revelation as cinema and the world’s greatest rock festival grew up alongside each other. Thank you to all associated artists, organisers, filmmakers and art-lovers.

-Alex